Enrico Fermi, Albert Einstein, John von

Neumann, Niels Bohr: The legacy

of foreign-born scientists and mathematicians in America is well known.

They helped create the computer and the atom bomb, and

have

contributed a good portion of America's Nobel Prizes. Today, more than

half of all engineers with PhDs working here were born abroad, as were

45 percent of computer scientists and physicists with doctorates.

But according to a recent study, there's another, less

documented

benefit that many immigrants bring to math and science in this country:

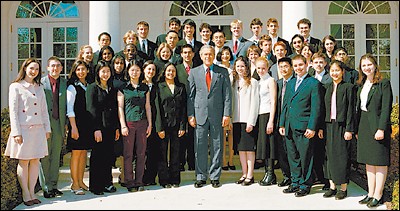

their children. While doing some research on the Intel Science Talent

Search (the "Junior Nobel Prize"), Stuart Anderson noticed a high

number of finalists who seemed to have recent immigrant roots.

When the director of the National Foundation for

American Policy

delved deeper, the results were even more striking. Seven of the Top 10

award winners in this year's contest were immigrants or their children.

Of the top 40 finalists, 60 percent were the children of immigrants.

And a striking number had parents who had arrived on skilled

employment, or H-1B, visas.

"The study indicates there are significant gains to

immigration that haven't really been realized," says Mr. Anderson.

"There's been controversy over employment-based

immigration, but if

we had blocked these people from coming in, two-thirds of the top

future of math and science wouldn't be here, because we wouldn't have

allowed their parents in."

It's no surprise to most people who follow such

high-level

competitions, of course, that children of immigrants are well

represented there, but even participants say they are surprised at just

how significant the trend is.

"It seems like a lot of the parents who are immigrants,

they've just

had to work a lot harder to get where they are right now," says Divya

Nettimi, a finalist in Intel whose research on the molecular compound

myosin furthered the understanding of muscle contractions. "In India,

such a huge focus is placed on education, because jobs are so scarce

that it's a question of survival."

Her parents, both software engineers, came to the US

from India when

Divya was 9 months old, in large part because they wanted more

opportunities for their children.

Anderson says immigrant parents view the science and

math fields as

good for their children because they're objective. "You don't have to

worry about the subjectivity that can creep into fields like politics,

or law, that are based on family connections or what you look like," he

says.

There's also the fact that many of the parents

themselves are

working in those fields. In fact, the numbers that arrived on the

professional H-1B visas is strikingly high. Of the 40 Intel finalists,

for instance, 18 had parents who came on an H-1B visa - more than the

16 finalists who had American-born parents.

The visas are a political hot potato, however. Between

the security

concerns after 9/11 and economic concerns during the recession, there's

been significant pressure to reduce immigration and tighten the

visa-granting process.

A National Science Foundation report issued this year

noted that

denial of high-skilled visa applications nearly doubled from 2001 to

2003, and universities have said fewer foreign students are applying.

The report also gave a stark warning about how the

future of US

dominance in research and development could be affected if the country

continues to lag behind in educating its own citizens in the sciences.

And this spring, 25 academic and scientific organizations, including

the National Academy of Sciences and the Association of American

Universities, issued a joint statement about the need for changes to

the granting of visas.

So far, however, the discussion has centered only on the

immigrants

themselves - not their children. Yet the notion that many of these

children are successful has been established for some time, says

Marcelo Súarez-Orozco, codirector of immigration studies at New York

University.

What's striking about the data, he says, is how

"bimodal" it is,

with immigrants' children trending toward both ends of the spectrum.

Studies have shown that today, they're more likely than ever to end up

at places like Princeton, or Harvard, or MIT.

"But at the other end of this distribution, there are

large numbers

that are struggling," says Dr. Súarez-Orozco. Immigrant children arrive

with an edge over their American counterparts, Súarez-Orozco says, but

"over time there is a relative decline in terms of optimism and energy."

Among the top students that Anderson looked at, however,

that optimism and energy are still very much in evidence.

Andrei Munteanu - whose parents came from Romania when

he was 13,

and who got the idea for his research on data to predict asteroid

collisions from watching the movie "Armageddon" - is excited about

starting classes at Harvard, which he chose over MIT because he "likes

other things" in addition to math and science. Like Divya, he credits

his parents with a lot of his success. "They gave me not pressure," he

says, "but encouragement."