homestead AT lists.ibiblio.org

Subject: Homestead mailing list

List archive

- From: Tvoivozhd <tvoivozd AT infionline.net>

- To: homestead AT lists.ibiblio.org

- Subject: [Homestead] The Lame Duck Presidency

- Date: Sun, 05 Sep 2004 14:46:20 -0700

Second terms: big

desire, little result

If Bush wins reelection,

history shows he may have to overcome fleeing staff, declining support.

| Staff writer of The

Christian Science Monitor

WASHINGTON –

As President Bush pushes hard for reelection, here's a bit of advice

many of his predecessors might agree with: Beware the second term.

This doesn't mean US chief executives can't get important work done up up until the end. That's when Bill Clinton began piling up government surpluses, after all. Ronald Reagan kept up pressure on the cracking Soviet Union.

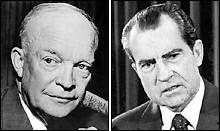

But history suggests that, on the whole, second terms become the spent volcanoes of US politics. Staff flee, public support dwindles, and bad things just seem to happen. Think just two words: Monica Lewinsky. Two more words: Iran-contra. Richard Nixon was forced out of office in his second term. Dwight Eisenhower had health problems. Harry Truman started fighting the Korean War. Cozy retirement in Crawford, Texas, may be looking better by the minute. "Second terms tend to be downhill," says Stephen Hess, a professor of media and governance at George Washington University. The reasons incumbents try for second terms are obvious, of course. Reelection validates their first term. There's unfinished work they want to do. Their staff and party structure push them to continue, usually. And come on, who would voluntarily give up Air Force One? That said, the pressures of office are undeniably wearing. Facing declining political support and the morass of the Vietnam War, Lyndon Johnson declined to run. As Mr. Bush knows, his own father lost 15 pounds and had trouble sleeping as the decision point for his reelection bid neared. George H. W. Bush's press secretary, Marlin Fitzwater, thought that following the end of the Gulf War the elder Bush's heart was no longer in it. "It seemed to me that he had a real feeling that he didn't want to run," Mr. Fitzwater later said. Ultimately Bush did try for a second term - and lost. Incumbents who win, for their part, tend to want to shake things up. They know that they won't face voters again and that their power may quickly wane with the onset of lame duck status. "History shows that presidencies are often remade in a second term," notes a Brookings Institution study of governing styles by noted scholar Charles O. Jones. They're often remade from the top down. Most modern second terms have begun with a Cabinet shuffle - and Bush is likely to be no exception if he wins. Few in Washington expect Secretary of State Colin Powell to serve four more years, for example. National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice might be a candidate for his job. Homeland Security chief Tom Ridge has hinted he might also hit the highway out of town. And if he leaves, who would be better to fill his wingtips than Rudolph Giuliani? But too much change can be counterproductive. Upon his reelection in 1972, Richard Nixon asked for wholesale resignations from his Cabinet members and top aides. "The result was demoralizing and confounding," concludes the Brookings Institution study.

Following turnover at the top, second terms generally experience another personnel trend - exodus at the bottom. Experienced mid- and low-level aides flee for the private sector and shorter hours and higher pay. They know their value to employers partly lies in their contacts with and knowledge of the administration in power. "These are people who say 'I better get out now,' " says Mr. Hess. Already, research shows that in general White House aides now stay in office only about half as long as their predecessors of the 1950s. The upshot: By the end of a second term, many who know how to get things done have left, and their replacements aren't yet fully up to speed. Domestic policy agendas often similarly suffer from a kind of burnout. The things presidents wanted to do, and could get through Congress, have been done. What's left are small items that can present the illusion of progress but don't really do much (think Bill Clinton and his many small-governance initiatives) and big items that couldn't get through in the first place. President Bush, for instance, has vowed that he'll continue to press for Social Security reform via partial privatization in a second term. Well, join the club: Pretty much every second-termer since Johnson has promised to shake up Social Security - and failed. Constrained at home, presidents have often become preoccupied with foreign affairs in second terms. Sometimes, that's a good thing. Eisenhower left office a popular figure. Reagan's Soviet policies helped end the cold war - although his inattention to the fact that his aides were selling arms to Iran to raise money for the Nicaraguan contras cast a pall over his final White House years. But for every Ike there's a Johnson - a president weighed down at the end by the problems of the world. Truman had the Korean stalemate, for instance. Then there's James Madison. His second term coincided with the latter stages of the War of 1812. In 1814, the British invaded Maryland, broke through to Washington - and burned down the White House, Madison's home.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- [Homestead] The Lame Duck Presidency, Tvoivozhd, 09/05/2004

Archive powered by MHonArc 2.6.24.